Vietnamese Dong: Guide to Vietnam Currency

Vietnam, the long S-shaped country stretching over 3,000 km from north to south, is a top destination for travelers and expats seeking a blend of natural beauty, rich history, and vibrant culture. From the busy streets of Ho Chi Minh City to the serene waters of Halong Bay, tourists flock to Vietnam’s world-renowned tourist sites each year.

Anyone planning to visit this beautiful country, nicknamed the Land of the Blue Dragon, should understand the Vietnamese currency, the Vietnamese Dong (VND). In this all-in-one guide, we’ll explore the Dong’s history, its denominations and banknotes, and share practical tips for exchanging money and using cash on your trip.

A Brief History of Vietnam & Its Currency

The first historical evidence of people in the Vietnam region dates back to 2879 BCE, with the emergence of the Hong Bang Dynasty, when the first Hung King united all the local tribes under one rule for over 2500 years. After its decline, China began encroaching on the kingdom of Vietnam. Until 544 CE, there was a perpetual struggle among the local Vietnamese peoples, tribes, and the Chinese rulers.

Finally, the Vietnamese took control, and the Ly dynasty began its rule under Emperor Ly Nam De, until 602, when the Chinese took control again. This back-and-forth struggle with many other groups, including the Chinese, the Mongols, and other surrounding groups, continued for centuries. One high spot during the medieval period of the country is 1418. A wealthy philanthropist by the name of Le Loi sparked the Lam Son Uprising against the Chinese.

The uprising was successful, and Le Loi became emperor in 1428, establishing the Le dynasty. Under Le’s leadership, one of his companions, scholar Nguyen Trai, wrote the Great Proclamation – a document that created an undercurrent and spirit of independence and nationalism that kept the Vietnamese people united in all future occupations.

Colonialism and the Modern Era

Le’s dynasty, like those before, was short-lived. Portuguese explorers discovered the area in the 1600s, exposing this part of the world to the rest of the European continent. Then, in 1858, France took control of Vietnam, making it a French colony. The French would remain in control up to World War II, when the Japanese would step in after the French were defeated by the Germans.

It was during World War II that Vietnam saw the rise of Ho Chi Minh with the founding of the Communist Party of Vietnam. The rise of this personality would eventually lead to the breakup of Vietnam into North and South, along with US involvement in the Vietnam War. The Vietnam War era created a lot of chaos for the nation, ultimately leading to a Communist takeover and unification of the country.

The remainder of the 20th century led to unification between the North and South. Eventually, the US ended economic embargoes, and the Communist government softened, allowing economic prosperity to begin slowly. Today, Vietnam is still under communist rule, but it is a softer hand and is similar to that of China, with a population of around 96 million people.

Market forces are allowed to move within the country, but the government keeps a strong hand. To demonstrate their commitment to economic activity, a stock exchange was opened in 2000. The opening of Vietnam to the rest of the world has created an infusion of capital and resources that make the currency attractive and poised for economic growth.

History of the Vietnamese Dong

Vietnam’s currency history is rich and complex, shaped by colonialism, war, and reunification. During French colonial rule, Vietnam used the French Indochinese piastre. After independence in 1945, the Viet Minh government in the North introduced the dong in 1946 at par with the piastre. The North’s new currency circulated alongside a separate South Vietnamese currency under the Saigon regime.

In 1951, President Ho Chi Minh founded the Vietnam National Bank (VNB) to manage money and issue banknotes. In 1961, the VNB was renamed the State Bank of Vietnam. Meanwhile, the war-torn country had two currency zones: North and South. After the fall of Saigon in April 1975, the Communist government immediately moved to unify the currency. Former South Vietnamese notes (the “Saigon regime” dong) were exchanged for new North Vietnamese dong at a rate of 500 old dong for 1 new. The Dong was officially unified nationwide in 1978.

Inflation soon took hold. The Dong was revalued in 1985 (1 new dong = 10 old dong), but this did not stabilize prices. Vietnam’s economy gradually opened up in the late 1980s and 1990s, but the Dong remained weak, requiring larger and larger banknotes. By 2003, Vietnam introduced a 500,000-dong note (roughly US$25) and began printing higher denominations on polymer for security.

Today, the State Bank of Vietnam (the successor to the Vietnam National Bank) issues the Vietnamese Dong – the Vietnamese currency we know and use today.

Ready to sell?

Are you ready to sell your currency? Stop waiting and request a Shipping Kit. We will provide everything you need to ship and receive funds for currencies you own.

Vietnam Currency: Dong Banknotes & Coins

The currency code for the Vietnamese Dong is VND, and the currency symbol is ₫. The name of the currency, "Dong," originates from the term "dong tien," meaning money. It is a loan word from the Chinese, referring to bronze coins that the Chinese used during their control of the country.

The Dong was historically printed by a mint in Finland, but, most recently, in Australia, which has provided Vietnamese money with holographic technology on their bills. As the modern economy emerged, Vietnam struggled with currency counterfeiters. To combat this rising problem, the government has implemented some of the best currency security features in the world.

Vietnamese Dong Banknotes

-

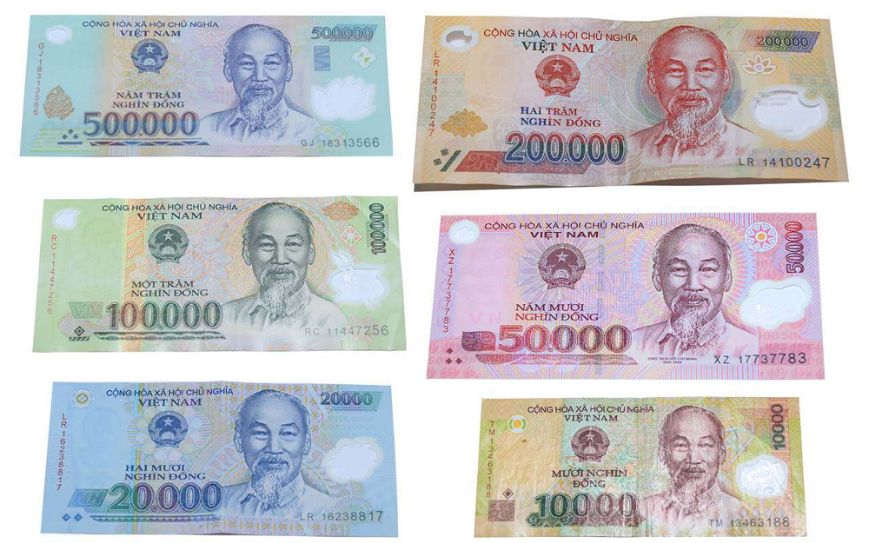

Banknote denominations: ₫100, ₫200, ₫500, ₫1,000, ₫2,000, ₫5,000, ₫10,000, ₫20,000, ₫50,000, ₫100,000, ₫200,000, ₫500,000.

The Vietnamese currency comes in many banknote denominations from 1,000 VND up to 500,000 VND. Commonly used notes include ₫1,000, ₫2,000, ₫5,000, ₫10,000, ₫20,000, ₫50,000, ₫100,000, ₫200,000, and ₫500,000.

Lower paper notes (100–5,000 VND) exist but see almost no use in practice. As of 2024, the 500,000-dong note (dark blue) is the highest in circulation. Typical travelers will use notes from 10,000 VND (about US$0.40) up to 500,000 VND (about US$20).

Vietnamese Dong Coins

-

Coin denominations: ₫200, ₫500, ₫1,000, ₫2,000, ₫5,000 (seldom used).

Vietnamese money is overwhelmingly paper; coins are practically defunct due to inflation, and did not even exist until 2003. In theory, there are coin denominations of ₫200, ₫500, ₫1,000, ₫2,000, and ₫5,000, but these low‐value coins are rarely seen in everyday use.

In fact, coins have not been circulated for purchases since about 2011. Instead, merchants simply round cash transactions up or down. Vietnamese and frequent travelers have gotten used to this practice and do not reject the custom.

Vietnamese Dong Notes Come in 2 Families

Vietnamese Dong banknotes belong to one of two “families”: cotton (paper) notes and polymer notes. Paper (cotton) notes are of low value and no longer produced. VND$200, VND$500, VND$1,000, VND$2,000, and VND$5,000 fall into this family, but they range in value from less than a penny to $0.22 in current USD values. These banknotes are easily torn and damaged by water, which only adds to their already low value.

Locals often collect these notes to gamble with them during the holidays, like Tet, the Vietnamese New Year. Today, Vietnamese Dong is no longer printed with cotton paper, but with a special polymer designed to deter counterfeiting. It is considered an exotic currency, just like the Iraqi Dinar or Indonesian Rupiah. Polymer notes (printed on plastic) last longer and are worth more, used for larger denominations.

Currently, polymer banknotes are issued for ₫10,000 and above, while cotton paper notes cover ₫5,000 and below. Polymer bills also have advanced security features, such as holograms and transparent windows to prevent counterfeiting. If you’re traveling to Vietnam, you’ll likely use the 50,000 note the most. Currently, it’s worth around USD 1,90, with which you can buy a full meal plus a drink and dessert.

What Do They Look Like?

Vietnam’s banknotes are colorful and feature cultural imagery. All modern Dong notes display the portrait of President Ho Chi Minh on the front, along with the national emblem. The reverse of each note shows famous tourist sites and landmarks, reflecting pride in Vietnam tourism.

For example, the ₫20,000 note (bright yellow) depicts the historic Japanese Covered Bridge in Hội An. The ₫50,000 note (pink) shows the ancient Imperial Citadel of Huế, and the ₫200,000 note features Halong Bay. Learning these designs can help you quickly recognize denominations.

However, because the Dong is so weak compared to other currencies, prices come with many zeroes. For everyday budgeting, many travelers use a currency converter to make sense of costs in their home currency. For example, a typical street meal might cost 50,000–100,000 VND (about US$2–4). Note that as of August 2025, one US dollar buys roughly 26,000 VND.

Exchange rates can fluctuate, so always check real-time rates before spending or exchanging your currency. You can also always turn on custom exchange alerts for the Vietnamese Dong (or any other currency we offer) to keep track of the spot rate.

Tips for Travelers: Using Money in Vietnam

-

Carry Local Currency

While some businesses might accept US dollars as “foreign currency” in big cities like Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi, it’s a gamble, and you should plan to pay most expenses in Dong. Some local hotels, restaurants, and tour operators might accept USD (sometimes even displaying prices in dollars). However, once you leave the big cities, virtually every transaction is in Dong.

Street vendors, buses, markets, and most smaller shops will not take USD – they expect local currency. In fact, it’s a good idea to have some Dong on hand the moment you land. Consider buying a small amount of VND to have on hand upon arrival so you can pay for taxis and vendors right away, while avoiding the costly ATM fees.

-

Where to Exchange Money

You have a few options to get Dong: banks, licensed exchange bureaus, ATMs, or online currency services, such as US First Exchange. Banks (such as Vietcombank, VietinBank, etc.) offer reliable service but often require presenting your passport and may charge a fee. Currency exchange offices (often found in airports or tourist districts) are convenient, but exchange rates may be less favorable.

Avoid unlicensed money changers and street currency exchange stalls, even if they tempt you with extra-high “bargain” rates. Such stalls in tourist areas can be scams or hand you counterfeit or short-counted bills. If you must, you can get Vietnamese currency at:

-

At airports, you will find official exchange counters (e.g., VietinBank booths at Tan Son Nhat Airport). These are safe but notoriously poor-rate and often tack on extra fees. Only use the airport exchange in an emergency.

-

Authorized bureaus and gold shops in the city usually have better rates. Licensed jewelry stores often do currency exchange and can offer competitive rates.

-

Licensed money changers and banks in cities.

-

ATMs: To minimize foreign transaction fees, withdraw in Dong (not in USD) and pay any ATM fees your bank charges.

However, be aware of exchange rates and fees with each method.

-

Use Credit Cards Selectively

Credit cards (Visa/MasterCard) are accepted at many hotels, upscale restaurants, major tourist sites, and large stores in cities. However, paying by credit card is still uncommon in many places. Small restaurants, markets, and rural businesses usually require cash. Always carry some cash (Dong notes) for these situations. If you do use a credit card abroad, watch out for foreign transaction fees (typically 1–3% of each purchase).

-

Tipping & Handling Cash

Vietnamese Dong banknotes, especially polymer ones, can stick together or be slippery. Learn to fan them out and always count your change carefully. Street vendors may not have change for large notes, so carry a variety of denominations.

In Vietnam, it’s not customary to tip like in the U.S., as tipping is not deeply ingrained in Vietnamese culture like in some Western countries. It's a gesture of appreciation rather than an obligation. Keep extra ₫50,000–₫100,000 notes for small tips or incidentals.

Where to Get Vietnamese Dong

For investors, collectors, or travelers, the Vietnamese Dong is an interesting currency to purchase. Vietnam is an emerging economy, and as the region has stabilized, it has seen an influx of foreign investments. If you’re traveling to Vietnam and looking to buy Vietnamese Dong in advance, one safe option is to order it online.

At US First Exchange, you can buy foreign currency online at competitive rates and have it shipped straight to your door, safely and within 24-48 hours, meaning you can arrive in Vietnam with spending money already in hand. This can be more convenient and secure than exchanging USD for Vietnamese currency upon arrival. You’ll lock in the best rate and avoid airport rush and high fees.

All shipments are fully insured, and we pride ourselves on having the industry’s lowest spreads. To provide the most secure and safe transactions, US First Exchange is registered with the US Treasury as a Money Services Business (view a copy of our registration). In addition to federal regulation, we hold multiple state-specific licenses as a money services business. Where required, we are bonded as well, for your peace of mind.

Vietnamese Currency FAQs

Anything else on your mind regarding currency and money in Vietnam?

How Much Is $100 US In Vietnam Dong?

As of 2025, $100 US dollars is equal to about 2,500,000–2,600,000 Vietnamese dong (VND), depending on daily exchange rates. Rates fluctuate, so it’s best to check a live currency converter or a trusted currency exchange service like US First Exchange before traveling.

Should I Get Vietnamese Dong Before Going To Vietnam?

Yes, it’s recommended to get at least some Vietnamese dong before you travel. Having cash in the local currency makes it easier to pay for taxis, food, or small purchases right after you land. You can order Vietnamese dong safely online from US First Exchange, which delivers it to your doorstep at competitive rates.

Once in Vietnam, you can also withdraw dong from ATMs or use authorized currency exchange stalls and banks, but expect more fees and lower rates.

What Can You Buy In Vietnam With 1000 Dong?

1,000 Vietnamese dong is worth just a few US cents, so it has limited buying power today. In some rural areas or local markets, 1,000 dong might buy a small plastic bag at a shop, a single candy, or a few peanuts. In most cases, prices in Vietnam start at around 5,000–10,000 dong for small items like bottled water or street snacks.

Is $100 A Lot Of Money In Vietnam?

Yes, $100 goes a long way in Vietnam compared to the US. With about 2.5 million dong in your pocket, you could cover several days of meals, local transport, and even budget accommodation. For example:

-

Street food meal: 30,000–60,000 VND ($1–2.50)

-

Coffee: 20,000–40,000 VND ($0.80–1.50)

-

Budget hotel room: 400,000–700,000 VND ($15–30 per night)

While $100 is not “a fortune,” it is definitely a significant amount for travelers and can cover daily expenses comfortably when in Vietnam.

Ready to buy?

Are you ready to buy your currency? Stop waiting and request a Shipping Kit. We will provide everything you need to ship and receive funds for currencies you own.